Borrelia burgdorferi

Pathogen Life Cycle

This page was produced as an assingment for an undergraduate course at Davidson College.

B. Burgdorferi commonly infects mice, squirrels, and other small rodents, but the pathogen is spread to humans through tick bites. The species of tick responsible for causing Lyme disease varies based on geographical location. The deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) of the northeastern and north-central United States as well as the western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus) of the Pacific coastal United States are both common vector hosts of B. burgdorferi (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/lyme/ld_transmission.htm). Lyme disease in Europe is caused by the European sheep tick (Ixodes ricinus), and the Ixodes persulcatus tick species causes Lyme disease in China and Japan. A human’s risk of contracting Lyme disease through a particular tick depends on the feeding habits and population density of the particular tick (Steere, 2001).

Blacklegged Tick (Ixodes scapularis): causative agent of Lyme disease in humans

Photo courtesy of NIH [http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/research/topics/lyme]

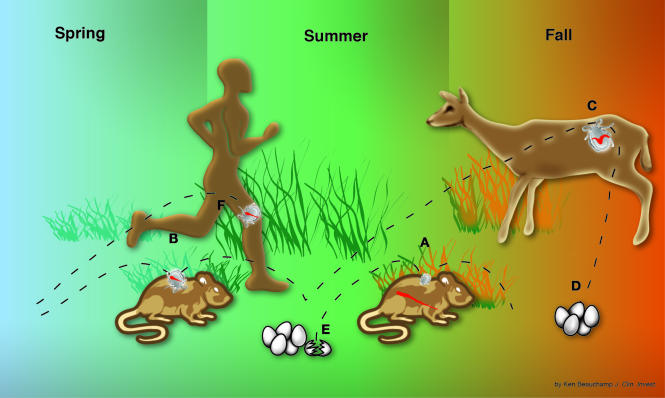

Ticks have a four-stage life-cycle: egg, larvae, nymph, and adult. The transmission of B. burgdorferi from rodent to human occurs when a young tick bites a B. burgdorferi-infected rodent, ingesting the bacterium with the blood meal. The bacterium then resides in the tick’s gut, and if the tick should feed again, it can pass the bacterium to its new host. (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/lyme/ld_transmission.htm). Larval ticks typically feed on small rodents and then molt into nymphs, while nymphal ticks feed on small animals and sometimes humans and then molt into adult ticks. Adult ticks feed on larger animals, usually deer, after which the female tick drops her eggs to the ground for the cycle to begin once again (Diterich and Hartung, 2001). Ticks in the nymph stage most often transmit B. burgdorferi to humans, and the tick must be attached for 24-48 hours in order for B. burgdorferi to be successfully transmitted to humans (Re et. al, 2004).

Tick size at each stage of the life cycle: Blacklegged Tick, Lone Star Tick, and Dog Tick

Image courtesy of the CDC [http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/lyme/ld_transmission.htm]

Image courtesy of http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/dtopics/tickborne/twoyrcycle.html

Image courtesy of http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/dtopics/tickborne/twoyrcycle.html

Enzootic cylce of Borrelia burgdorferi infection

Image courtesy of http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=385417

The differential ability of nyphmal and adult ticks to infect is based on their salivary glands. The salivary glands of nyphmal ticks are highly infected with B. burgdorferi, while the salivary glands of adult ticks are virtually free of spirochetes (Burgdorfer et. al, 1989). In addition, the spirochete stays in the midgut of the tick vector, habitating the microvilli and epithelium of the gut (Burgdorfer et. al, 1989). While the gut is the main site of bacterial residence, after feeding the bacteria can evade the gut epithelium and make its way into the salivary glands of the nymphal tick, allowing it to infect other hosts (de Silva and Fikrig, 1997).

Experts dispute the method of bacterial delivery from the tick vector to humans and other hosts. One argument is that the pathogen is spread directly via infected saliva. Another supported argument is that ticks with infected midguts transmit the bacterium through frequent regurgitation of gut fluid, especially during feeding (Burgdorfer et. al., 1989). The bacteria remain at the injection site for a short time, and then spread throughout the body to various organs and tissues of the host. (Philipp and Johnson, 1994).

This page was created for an undergraduate Immunology course, Biology 307, at Davidson College in the Spring semester of 2007 under Dr. Sophia Sarafova (sasarafova@davidson.edu)

Please direct all comments and questions to Meredith Prasse (meprasse@davidson.edu)